It was my second day in Berlin, a solo trip that started without any plans and hopes that spontaneity and good luck would guide the way. The first day had already set the tone. On the train, I met a girl who very passionately told me about her dreams, hobbies, travels, even Polish politics, about how her parents met, without the slightest interest in learning anything about me. After an hour and a half she finally asked her first question, and I couldn’t resist pointing out that it was her first. We laughed as the train crawled us into Berlin where we parted ways.

Later that evening, I stepped out of the apartment for a stroll, and there she was again in her full glory, celebrating a birthday with her friends. How surreal is that, meeting the same stranger twice in a city of four million? I joined them for a while, had a few good conversations, and slipped away. I kept wondering: why twice?

Encouraged by the events of the first day, I hopped on a city bike and pedaled aimlessly. Soon, I found myself in a shawarma shop with my journal in front of me, putting down whatever my wild mind guided my pen to scribble. I couldn’t help but close the entry with Ghalib’s masterpiece:

بک رہا ہوں جنوں میں کیا کیا کچھ

کچھ نہ سمجھے خدا کرے کوئی

O, how i prate in frenzied state,

let none grasp my meaning, o lord.

I shoved the journal back in my tote, wandered along the river, and was drawn towards a colorful Tibetan food truck selling momos. While I was talking to the seller about Tibetan meditation practices, the Dalai Lama, she suddenly asked me if I’d like to meet an ex-monk with 29 years of practice and a PhD? I couldn’t quite believe my luck. “Are you kidding me? Hell yeah!” was what I wanted to tell her, but “yes, please” was what I managed.

Five minutes later, I was sitting beside the man himself. His story began with tragedy—fleeing home at 17 because of the Chinese occupation. He laughed telling me about sneaking out of the monastery to watch football, ducking the monk police. He explained how monks could only beg from three houses; if nothing came, you went hungry, and learned to be content with reality showing itself that way.

I was gearing up to navigate through the different masks, but I realized pretty early on that there were no masks to begin with. I can see through everything like a transparent lake on a sunny day. He later told me that when he had to get the German Visa, he told the Visa officer about all the incorrect information in his passport. And yet, he still got the Visa. It seemed like the man didn’t even know how to lie.

Sifting through different parts of the monkhood, we reached the beginning of the end which is where things became a lot more interesting. He started telling about his life in Shimla where he was studying English. He would have some small chats with an American woman sharing the same hotel. One day she made advances. He requested her to respect his monkhood. Nothing happened but that was when he could see parts of himself that he didn’t face before. He had the desire to reciprocate too, but his discipline overpowered the storm that was brewing within.

But not for long, there were soon ripples in the calm lake with the connection that was slowly building between him and the English teacher. My man tried his best to keep to his vows, including maintaining a distance for a while. But in the end the connection won, the love won. They stayed in a hotel for a week and only after a week he somehow knew he was going to be a father. And he was not wrong.

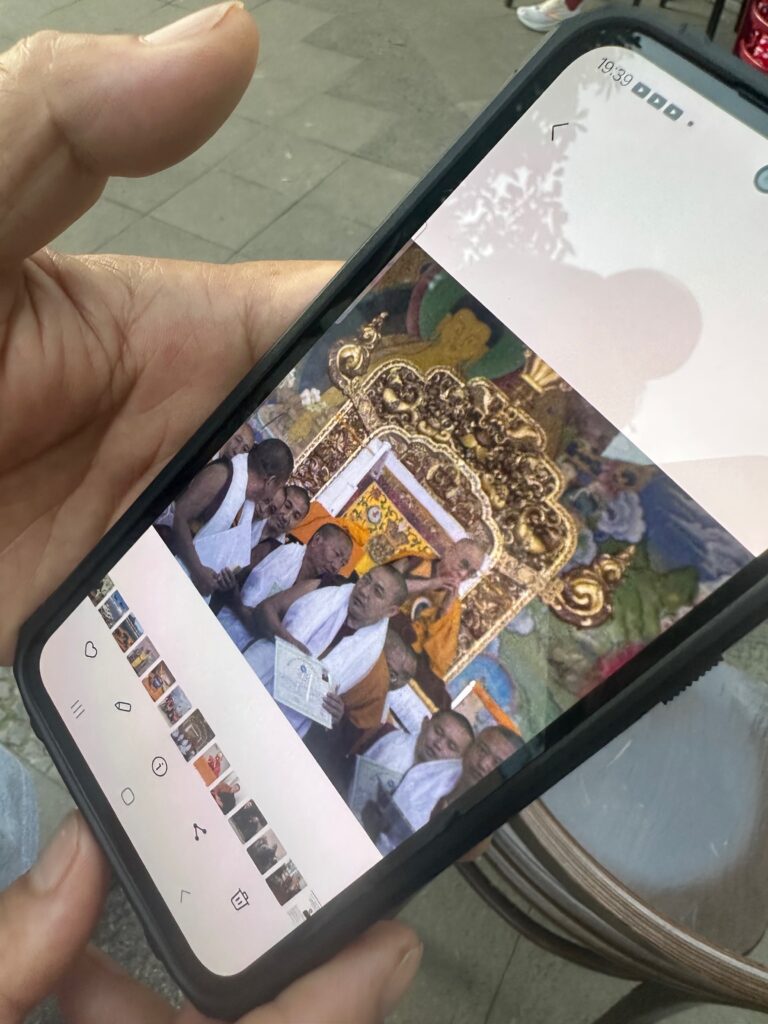

He moved to Germany to be with his wife. They had a son who is now seven. But life outside monkhood carried its own challenges. The monk from the East couldn’t make it work with the modern western woman. They eventually separated, though still managing a deep friendship. He showed me photos of his ex-wife and his son currently traveling in Tibet.

What stayed with me wasn’t just his story, but the way he told it—with such purity, such simplicity. Twenty-nine years of daily practice, and still, behind it all, he was just human.

Before leaving, he hugged me, said he’d love to visit me in Finland, and disappeared into the evening. I kept walking by the river, spoke with a German railway engineer, and finally trudged back home, listening to the great Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan singing Iqbal’s wisdom:

تو رہ نورد شوق ہے ، منزل نہ کر قبول

If you traverse the road of love, Donʹt yearn to seek repose or rest

And as the night settled, I wondered—had I really met them, or only the different parts of myself wandering through Berlin?

Leave a Reply